Introduction

This article is about requirements engineering in publicly funded, large scale research projects, as we find them particular in many ways. First, the common setting of such projects is that multiple organizations from various industries partner with multiple research bodies – governmental and non-governmental – in order to achieve a pre-set long-term research goal. Secondly, the funding application is usually drafted by a team of senior researchers and managers with the funding body as audience rather than the potential stakeholders in mind. Thirdly, the time span between handing in the application and the project start can be as long as a year, thus people who had worked on the initial application might already be assigned to other projects by the time the project is kicked off. Hence, it is often the newly hired who work on the project with little to no familiarity with the funding application. Fourthly, the (newly established) teams have to execute what is written down in the Grant Agreement, a very detailed document often over 100 pages, stating deadlines, approaches and content of tasks, building a binding contract between the funding body and the project consortium. Considering all these factors combined, experiences from various publicly funded projects show that the requirements engineering phase in such a setting presents different challenges than in other projects.

Investigating the literature, we find only limited research looking at these challenges. To our best knowledge, there are only three papers which explicitly look at requirements engineering in publicly funded research projects: Przybilski (2006) discusses the suitability of the Wide Audience Requirements Engineering (WARE) method in international research projects. Outlining the specific settings and the advantages of the method, the paper does not, however, go beyond a mere theoretical discussion. A case study applying the method in practice, on the basis of which the methods suitability could be discussed, is still missing. A second study we identified approaches the topic from a large-scale, security-oriented research project perspective (Gürses et. al, 2013). The paper outlines the challenges associated with such projects in detail and discusses the inapplicability of existing requirements engineering methods. Lastly, Pierce et. al. (2013) describes the requirements engineering process of a European funded project and argues in line with Gürses et al. (2013). As an addition to Gürses et al. (2013) the authors argue in favor of a requirements authority, validating and controlling access to the requirements data.

Disagreeing with Pierce et al. (2013) where a requirements engineering authority is recommended and in line with Gürses et al. (2013), we aim within this article to share our experience from an industrial practitioners’ perspective and with this contribute with a new case study to the undeservingly under-researched field of requirements engineering in large scale, publicly funded research projects.

The Case Study

The case study we describe is situated within the Smart Water management research project iWIDGET, which is funded under the EU 7th Framework Program. The aim of the iWIDGET project is to advance knowledge and understanding on smart metering technologies in order to develop novel, robust, practical and cost-effective methodologies and tools to manage urban water demand in households across Europe, by reducing wastage, improving utility understanding of end-user demand as well as reducing customer water and energy costs. The main scientific challenges for iWIDGET are the management and extraction of useful information from vast quantities of high-resolution consumption data, the development of customized intervention and awareness campaigns to influence behavioral change, and the integration of iWIDGET concepts into a set of decision-support tools for water utilities and consumers, applicable in differing local conditions. iWIDGET embraces the expertise of nine organizations from various European countries. Partners are universities, governmental research institutions, water provider and industrial research centers namely SAP, IBM, UPL, HR Wallingford, Águas de Barcelos (AGS), Waterwise, University of Exeter, Laboratório Nacional de Engenharia Civil (LNEC), University of Athens.

Our data collection procedure embraces the triangulation of qualitative instruments over 6 months: Eight semi-structured expert interviews, 12 fragments of field notes and relevant project documentation. Our results come with the usual limitation a single case study approach inherits (Yin, 2002). For readers additionally interested in the research done on requirements engineering in research projects in the context of iWIDGET, please consult the related publications: Grimm (2014), Özcan (2013).

Food for Thought

The context outlined in the introduction demonstrates how research projects differ from other development projects. In the following we share our thoughts on the challenges we found most dominating in publicly funded international research projects in the context of the requirements engineering phase: (1) Reassessing competences and managing intercultural communication, (2) the missing stakeholder perspective and (3) managing uncertainties.

Reassessing Competences and Managing Intercultural Communication

As set out in the introduction, the teams who had compiled the funding application most likely differ from the actual project team. In consequence, the team in each organization as well as the project team of the research project need to form first – and this complex finding phase happens at the same time as the requirements engineering phase starts, right at the beginning of a project. In addition, it might be that some teams have never participated in a requirements engineering phase before, despite them being formally assigned to the task. To support this phase and to not lose the time that shall be dedicated to the requirement engineering task to misunderstandings and discussions, we recommend that the project coordinator analyzes the concrete teams participating in the project regarding their interests and capabilities right at the start of the project – and not assume that if an organization is assigned to a task that the team is able to actually execute the work. Consequently, the project coordinator can recognize competences of partners before assigning specific responsibilities and see where training and reassignments are needed. The gap between the planning done in the course of writing the Grant Agreement and the reality shows itself quite clearly in this early stage of the project.

In the case study, the project failed to analyze the interests and capabilities of the actual teams at the start. It has been -naturally- assumed that teams assigned to the requirements engineering task according to the Grant Agreement can execute it. However, practice has proven this assumption to be incorrect. Some teams had no experience at all in requirements engineering and the resulting deficiencies in knowledge have only been recognized later on in the project, leading to misunderstandings and wastage of valuable time.

In the course of carrying out such an analysis of competences, communication interfaces between groups can be identified and included in the project planning as a task “to be monitored”. In the context of identifying communication interfaces, it might be useful for each team, as well as the project coordinator, to talk to the senior staff who compiled the funding application, in order to understand in detail the initial purpose of the project as well as existing informal communication channels and unrevealed agendas. Given the potential long time span between writing the funding application and the project start, the challenge with this task might be that some senior stakeholders are not available anymore and/or do not recall the specific details.

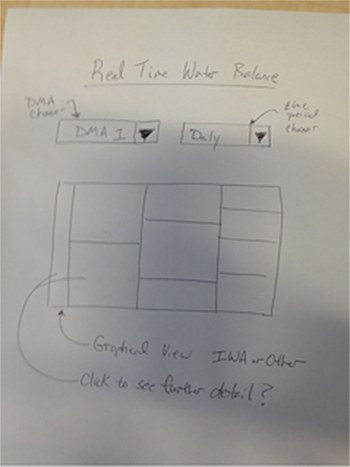

To ensure continuous communication between all parties throughout the requirements definition phase (and possibly beyond), we recommend showing flexibility in terms of choice of communication channels as well as templates. In the case study, it was shown that in this context a general openness to alternative communication channels is a plus. As an example, for iWIDGET the communication came to a stop during a workshop as the domain experts did not understand what the technician wanted to know and vice versa. Interestingly, the emerging gap could be managed by simply changing the way of communication: Instead of talking in a larger group, small groups were formed with a representative of each area. For each small group, a paper and pencil approach was chosen to draw the scenarios (see Figure 1) and directly discuss them. Some groups had to sit in the hallway and on the stair case, however; this only seemed to add to the spontaneously unfolding creativity.

The drawings helped all groups to actively discuss the cases and to build up a long term understanding for occupational communication specificities. The idea of using mockups became so popular that the project team continued to use them also to validate end results. An example of such a mockup is displayed in figure 2.

Overall, a continuous openness towards different templates and methods has proven useful, despite the extra work needed to bring all the information together. With a short learning curve team members who had been unfamiliar with the ideas of requirements engineering found it eventually easier to engage in the process.

Even though only taken care of informally in the case study, theories on working in cross-cultural teams, such as for example Hofstede (Hofstede, et al., 2010) or Adler (Adler, 2002), were shown to be profitable. The heterogeneity of participants provides the potential for the team to achieve higher productivity and creativity (Adler, 2002); however, at the same time, it can easily result in misunderstanding and slight chaos. Acknowledging differences and generating awareness of differences is a first step. This might be done in an explicit session on cultural values and / or in the context of recurring reminders in project calls to maintain awareness. Flexibility of the mind and striving for absence of prejudice need to be directly and indirectly communicated and practiced in such settings.

Overall, communication as well as recognizing competences is key to a project’s success. Where communication between the different parties fails in the course of the requirements engineering phase, ill-defined requirements are the result. As an analogy, where the end goal is to build a wheel, the consortium might end up with a fully fleshed out and nicely designed box. Thus it is vital to (1) identify the actual competences of the teams working on one task to avoid misunderstandings and delays due to a lack of knowledge (2) to watch communication channels (3) to show flexibly in modes of communication channels and templates and (4) to invest in understanding intercultural communication patterns and create an atmosphere of tolerance.

The Missing Stakeholder Perspective

Between the call for proposals and the proposal hand-in deadline often there is only a small time window of a few months. During this time, the consortium needs to be formed, meaning one organization starts to get in touch with potential partners to discuss the content and resource allocation. Together, the newly established consortium compiles the Grant Agreement and delivers it to the funding body.

The problem with this approach is that firstly, the time span between the call for proposals and the hand in deadline is rather short, thus there is no time to consult potential stakeholders such as end-users or buying centers. Secondly, even if there were time, it is unlikely that stakeholders would be consulted as it would be too resource-intensive to do this. With a success rate often lower than 30% (depending on the company and funding scheme), the team writing one application is most likely involved in writing other applications at the same time to increase the chances of winning new grants. To invest in contacting stakeholders, carry out workshops and analyze the data for each funding application would not be feasible.

Thus what the market wants is assumed by the funding application writing team. As the assumptions do not necessarily reflect the reality, it is vital to include stakeholders early in the project, to have their views translated into requirements. It is much more likely that requirements reflecting the stakeholders’ perspective lead to a marketable project outcome than requirements which were based on assumptions. In the case study it has proven profitable to prioritize contacting potential stakeholders before discussing details of requirements engineering, as waiting for a response and searching for alternative stakeholder representatives as well as scheduling meetings and interviews will take time.

Given the duration of the requirements collection phase in the light of the above mentioned challenges, our experience in iWIDGET, as well as in various other projects, is that the group responsible for system design and development may start designing before the requirements are available. In this case, the engineers would work on assumptions of what the market might want. While it seems logical to undermine such working under assumptions, the case showed that it can actually be profitable if it happens in a controlled atmosphere: The technicians’ early design and development efforts and related obstacles can be fed back to the requirements engineering team. The requirements can then be reflected upon in the light of the technical possibilities and trends. Thus, we recommend including this unusual effort in the project planning rather than trying to suppress it.

Managing Uncertainties

Research projects may differ from other projects in that the solution to the defined research problem is as yet unknown. Thus, the project duration and planning would need to reflect this uncertainty and allow researchers to explore different paths as well as respond to changes in the technological and political environment. However, in practice the situation is different: The content and deadlines of tasks are predefined in the Grant Agreement – regardless of the developments within and outside the project. With the Grant Agreement being a contractual agreement that firmly defines deliverable deadlines, changing the project’s timelines or scope can only be formally established in an amendment of the contract (and thus the Grant Agreement). For an amendment, however, all partners would need to agree on (1) the necessity of an amendment and (2) the scope and budget related to the amendment. In most cases, partners might be outright unwilling to make such changes as they require a large effort and lengthy discussions between all project partners, including the funding approval body. And even if the project team agrees on necessity, scope and budget, the funding approval body might still reject the request. Besides, any further additional amendments are most likely rejected from the start from all parties as the effort for one is already immense. If an amendment shall be avoided or is not possible, flexibility needs to be practiced informally. Milestone deadlines might be adapted as they are more flexible than deliverable submission dates, informal iterations facilitated and managed. Buffer times should also be planned where possible. In this context, knowledge of methods from agile project management might be an advantage. Again, already the awareness of this particular situation will help the project coordinators and work package leads to deal with the lack of needed flexibility.

Summary

Large scale international research projects challenge the way we know requirements engineering. The article aims to provide food for thought to practitioners from practitioners and a new case study for the academic research community. The focus has been on the specific things which we found make requirements engineering in research projects unique, such as the international and dispersed communication settings, the missing stakeholder perspective, and the general uncertainties resulting from the nature of the project as a research venture. We strongly believe that more research into this is needed in order to extend, test and evaluate emerging best practices. With only the Horizon 2020 program offering a total funding of 80 billion Euro, it might be worthwhile to invest some more time in research into the specific settings of requirements engineering in publicly funded research projects, as ill-defined requirements rarely lead to a successful, marketable project outcome. In the meantime, we hope this aide-memoire helps project managers in carrying out this challenging and most interesting task.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks go to Dr. Andrea Grimm, Dr. Uwe Riss, Dr. Oliver Kasten, Dr. Bradley Eck, Dr. Lydia Vamvakeridou-Lyroudia, Matthias Benz, Ronald Kramer, Santanu Chakraborty for valuable feedback.

References and Literature

- [1] Adler, N. J., 2002. "International Dimensions of Organizational Behavior 4th ed.." Cincinnati: South-Western College Publishing.

- [2] Bergman, M., King, J. L. & Lyytinen, K., 2002. Large-Scale Requirements Analysis Revisited: The Need for Understanding the Political Ecology of Requirements Engineering. Requirements Engineering, 7(3), pp. 152-171.

- [3] Coughlan, J., Lycett, M. & Macredie, R. D., 2003. Communication issues in requirements elicitation: a content analysis of stakeholder experiences. Information and Software Technology, 45(8), pp. 525-537.

- [4] EU Seventh Framework Programme, 2012. Grant Agreeement for the Project Improved Water efficiency through ICT technologies for integrated supply-Demand side manaGEmenT (iWIDGET), Brussels: EU.

- [5] Grimm, C., 2014. Final Report on iWIDGET, WP1 Requirement Analysis. [Online] Available at: www.i-widget.eu/publications.html [Accessed 04 September 2015].

- [6] Gürses, S., Seguran, M. & Zannone, N., 2013. Requirements engineering within a large-scale security-oriented research project: lessons learned. Requirements Engineering, 18(1), pp. 43-66.

- [7] Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J. & Minkov, M., 2010. Cultures and Organisations: Software of the Mind. 3rd Hrsg. USA: McGraw-Hill.

- [8] Hull, E., Jackson, K. & Dick, J., 2010. Requirements Engineering. s.l.:Springer.

- [9] Kavakli, E., 2002. Goal-Oriented Requirements Engineering: A Unifying Framework. Requirements Engineering, 6(4), pp. 237-251.

- [10] Özcan, O. G., 2013. Guidelines for Requirements Engineering in Research Projects (Unpublished master’s thesis). Zürich: ETH Zürich.

- [11] Pierce, K.; Ingram, C.; Bos, B.; Ribeiro, A., "Experience in Managing Requirements between Distributed Parties in a Research Project Context," in Global Software Engineering (ICGSE), 2013 IEEE 8th International Conference on , vol., no., pp.124-128, 26-29 Aug. 2013

- [12] Przybilski, M., 2006. Requirements elicitation in international research projects. AMCIS 2006 Proceedings, 535.

- [13] Robertson, S. & Robertson, J., 2006. Mastering the requirements process. s.l.:Addison-Wesley Professional.

- [14] Tuunanen, T.; Rossi, M., "Engineering a method for wide audience requirements elicitation and integrating it to software development," in System Sciences, 2004. Proceedings of the 37th Annual Hawaii International Conference on , vol., no., pp.10 pp.-, 5-8 Jan. 2004

- [15] Yin, R. K., 2002. Case study research: Design and methods. s.l.:SAGE Publications, Incorporated.