Howard Podeswa

The Business Case for Agile Business Analysis

What is Agile Business Analysis, and 10 reasons why it’s worth developing the competency within your agile organization

Over the years, I have often been asked to ‘make the business case for agile Business Analysis’. Sometimes it comes up in a meeting with executives, as it did a number of years ago at a North American telecom company, sometimes it’s a request to make a formal presentation to decision makers, as was the case for an international energy company, and sometimes the forum is a conference, such as the Norway Developer’s Conference, the Toronto Agile Alliance and, most recently at a BBC Conference in Las Vegas.

Before I address that question, let me begin by explaining just what I mean by Business Analysis (BA) and Business Analysts (BAs), by quoting the current definitions presented by the International Institute of Business Analysis (IIBA):

“Business analysis is the practice of enabling change in an enterprise by defining needs and recommending solutions that deliver value to stakeholders.” [1] (BABOK 3). A “Business Analyst” is simply “any person who performs business analysis tasks” [2]. Many (though not all) of the activities within BA overlap with RE, such as: Identifying Scope and Stakeholders, eliciting requirements, documenting requirements, validating requirements, resolving conflicts and managing requirements. So, in effect, the questions about whether Business Analysis has a future in agile – and what that future looks like – are also, to a large degree, questions about RE and its place within agile.

Those who have posed these questions to me have come from many places. Some belong to organizations that currently use BAs; they’re wondering whether it will make sense to continue to do so once they transition to agile. Some belong to agile teams who sense a potential benefit in including Business Analysts as they take on more demanding projects but are unsure how to integrate them – or even if it’s possible to do so. And sometimes the questions have come from Business Analysts who don’t even agree on the use of the term agile Business Analysis – as they see it as no different from good analysis practice. If you’ve wondered about any of these issues – or need to make the case to someone who does – read on.

What is Agile Business Analysis?

As its name (and definition) implies, agile Business Analysis is the love-child of two parents: Agile and Business Analysis. Figure 1, Agile and BA Time Lines indicates how these two approaches have co-evolved over a similar time period – with the items in green marking key points in agile development and the items in blue marking BA events. As the figure indicates, agile and Business Analysis trace their roots roughly to the 1980’s and ‘90s. Both were proposed as solutions to a problem that had been vexing software engineers at the time: A disproportionate number of software projects were deemed failures on every front. For example, the Standish Group 1995 Chaos Report found that “31.1% of projects will be cancelled before they ever get completed”, that “only 16.2% for software projects… are completed on-time and on-budget”, and indicated that “52.7% of projects will cost 189% of their original estimates”. [3] Business Analysis and agile development both attempt to improve this situation, but they proceed from different diagnoses.

The Business Analysis Prescription

Business Analysis proceeded from the assumption that the root issue of project failures was a communication problem between the business and solution providers. This assumption stemmed from research into the root causes of project challenges – such as the finding that the top 3 causes cited related to deficiencies in communicating business needs to solution providers: Lack of User Input; Incomplete Requirements & Specifications and Changing Requirements & Specifications [4].

In response, IT professionals began to address this shortcoming by developing a ‘Business Analysis’ practice with the aim of improving the requirements process in organizations. (I was one of the people at the time defining and developing the BA profession, through my work with the pioneering NITAS BA program created by CompTIA and the US federal government, as the designer of one of the first university corporate education BA programs in the U.S. and as a reviewer for the IIBA.)

Business Analysis was to a large degree derived from System Analysis – but with the technical aspects of the role removed and with other responsibilities related to Project Management added in, such as Stakeholder Management and scope control. Because the new BA role was non-technical (you didn’t need to be able to code to be a BA), it opened up the practice to people without a technical background – so that today many BAs come from the business side, placing those with a deep understanding of the business in control of the IT requirements – a fundamental change for many organizations and one that has reaped great benefits.

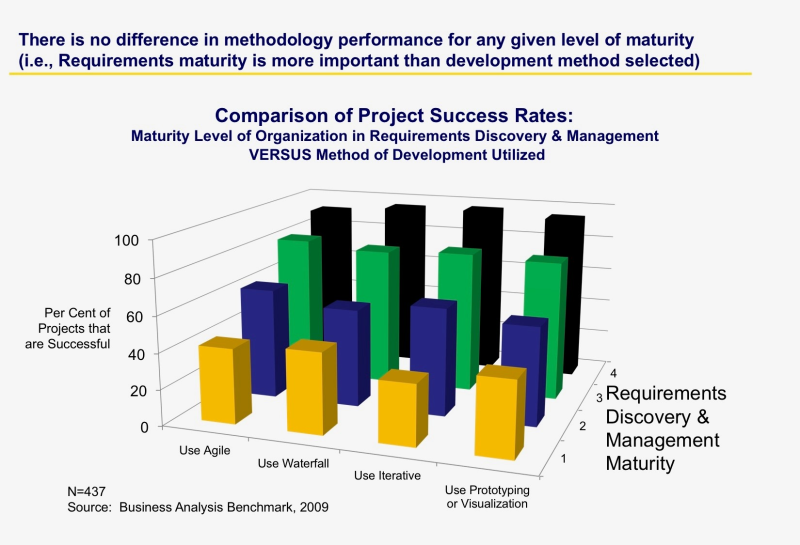

Today there is no question that improving the practice of Business Analysis improves project outcomes. One of the most scientifically rigorous studies of its kind, The Business Analysis Benchmark [5], was able to calculate a Requirements Premium – the added cost to a project attributable to poor requirements practices. It found that organizations using poor practices spent 62% more on similarly sized projects than organizations using the best requirements practices [6] (See Figure 2, Business Requirements Premium). Moreover, the study found that every measure studied improved as Requirements Discovery and Management maturity improved. (See Figure 3, Benefit Vs. Requirements Maturity Level.) Furthermore, according to the Standish Chaos Report 2015, 3 of the top 10 factors cited for project success are addressed by Business Analysis: User Involvement (which includes user feedback, requirements review, basic research, prototyping, and other consensus-building tools); Clear Business Objectives (which entails a common understanding of all stakeholders and participants in the business purpose for executing the project and aligning the project to the organization’s goals and strategy); and Optimization (a structured means of improving business effectiveness) [7]. One of those factors is also, unsurprisingly, the Agile Process – the other proposed prescription for the challenges facing projects.

The Agile Prescription

Agile proponents hypothesized that the root cause of project failures and challenges lay in the software development process itself – specifically, the ‘Waterfall’ lifecycle that was dominant at the time (and is still in fairly wide use today). Waterfall seeks to control scope and reduce rework by requiring each phase in the development process to be performed completely before the next step is allowed to proceed. Agilists have long noted an inherent flaw in this process: Since it demands that a thorough analysis and design be completed before the business sees any working code, it results in a long lag between the baselining of requirements and their eventual implementation. During that time, business needs and priorities are likely to change, with the result that the solution often fails even when it ‘meets the requirements’. To correct this flaw, agilists proposed replacing Waterfall with empirical process control – a trial and error process that uses repeated cycles of intervention and observation to arrive at a desired solution. A number of approaches were proposed and practiced in the 1990s – and these culminated in a meeting in 2001 that resulted in the formation of the Agile Alliance and a set of guidelines – the Agile Software Development Manifesto [10] – giving us the basis for what we refer to today as ‘agile’.

Today there is no question that agile is widespread and that it’s working. A 2016 survey found that agile adoption has “crossed the chasm and is in the early majority stage, most organizations are using agile techniques for at least some software development projects… and those who have made the mind-set shift, coupled with strong technical practices, have definitely seen measurable improvements in time to market, product quality and customer satisfaction” [11]. As I’ve noted, the same Standish Group 2015 Chaos Report that reported BA-related factors for success also cited Agile Process. And it provided positive metrics for agile initiatives across all project sizes: more agile projects were successful than Waterfall, fewer agile projects were challenged and fewer failed.

With respect to productivity, a QSMA study in 2015 found that ‘Agile projects experienced a 16% increase in productivity compared to [the] industry average’ [12]. (Productivity was measured as an aggregate of tooling and methods, technical difficulty, personnel profiles, and integration issues.) It should be noted that this productivity gain, while good news, does not match the far more extravagant claims made when Scrum was introduced – at which time the authors declared, “When we say Scrum provides higher productivity, we often mean several orders of magnitude higher i.e., several 100 percents higher.’ [13] However, on the measure that most executives I have spoken to care most about – time to market – agile’s gains are more impressive: The same QSMA study found that “Agile Projects are 37% Faster to Market than [the] Industry Average”. [14]

A Tale of Two Solitudes

With such a great track record for both BA and agile, you’d think that merging the two would be a slam-dunk. Although these two streams, agile and Business Analysis, got their start at around the same time they have been evolving in relative isolation from each other ever since, largely because they took root in different types of organizations: Business Analysis within large mainstream organizations and agile within tech startups. The two approaches began to bump up against each other when mainstream organizations started experimenting with agile approaches and, from the other direction, when the organizations and teams that were early adopters of agile began to grow to the point that they needed mature analysis tools to handle the complexities that came along with that growth.

These developments have brought the two solitudes of agile and Business Analysis together – and at the same time, provided the opportunity to birth a practice that inherits the synergistic benefits of its parents.

What Does Agile Business Analysis Look Like?

What does this new practice look like? One thing it does not look like is a unicorn – a fanciful creature we are never likely to see. I mention this because many do believe ‘agile Business Analysis’ to be an oxymoron, due to the popular view of BAs as people that perform big upfront analyses and create reams of documentation – practices that are diametrically opposed to the ‘minimal documentation’ and ‘just-in-time’ ethos of agile. In fact, though, Business Analysis has always been about doing just the right amount of work for the context; it’s just that the context for BA until recently has almost always been hierarchical, mainstream organizations, addicted to heavy planning and project governance. Now that these organizations have opened themselves to agile approaches, the BA function in that context looks much different. It is characterized by:

- Just-enough planning using light-weight tools such as the Product Canvas (to provide an overview of the Product and its rationale), the GO Product Road Map (for long-range planning) and Story Maps (for mid-term planning)

- Emphasis on conversation to capture requirements with “just enough” documentation using informal techniques such as User Stories and Use Case 2.0

- Light-weight requirement management processes based on the expectation of change.

- Just-in-time requirements analysis elicited incrementally and iteratively over the course of a project – rather than all upfront.

The frameworks and approaches that feed into the Agile Business Analysis discipline include Lean Startup, Lean Software Development, Scrum, Kanban, SAFe and XP as well as techniques developed by practitioners such as Richard Lawrence and Jeff Patton. Guidance related to the practice of agile Business Analysis can be found in a number of publications including the IIBA’s Agile Extension to the BABOK® Guide [15], User Stories Applied by Mike Cohn, and Agile Software Requirements: Lean Requirements Practices for Teams, Programs, and the Enterprise (Agile Software Development Series) by Dean Leffingwell. (I am currently working on a practical guide, to be published by Addison-Wesley, that walks the reader through an end-to-end agile initiative while focusing on the BA function.)

BA as a ‘role’ within agile

While those with a BA competency are often found today on agile teams, they are not always called ‘Business Analysts’ (partly because many agile approaches look down upon specialized team roles of any kind). So aside from “Team Analyst” and “Business Analyst” (called out explicitly in approaches such as DSDM), Business Analysis competencies are encompassed in a number of functions common within agile teams – such as the Proxy User (representing a user group), the Product Owner (many of whose responsibilities overlap with Business Analysis), and the Proxy Product Owner, who may be assigned to act in place of the Product Owner when there are not enough business stakeholders to go around. (See Figure 4 The BA mapped to agile functions, for an overview of agile positions that involve agile BA competencies.)

The Agile BA Track Record

We have seen that organizations that develop either an agile or a BA proficiency stand to benefit. What happens when they do both? The research shows that agile organizations that invest in developing a mature requirements discipline significantly improve outcomes. Figure 5, Per Cent Projects Successful Vs. SDLC and Requirements Maturity Level indicates how project success rates increase with requirements discovery and management maturity levels for all system development lifecycle approaches, including agile. In fact, the chart indicates a success rate that more than doubles when agile teams develop high requirements discovery and management maturity levels vs. those that maintain poor requirements levels.

10 Reasons It’s Worth Investing in Improving the Agile Business Analysis Competency within Your Agile Teams

We’ve seen that the research indicates that an agile team that improves its BA practice stands to gain impressive benefits with respect to project outcomes. What that research does not parse out is exactly why this is so. Over the years I’ve worked with many agile teams as they’ve matured their BA practice. In many cases, they had started out with agile coaches who didn’t spend much time on requirements analysis issues. The teams got by for a while with a bare-bones analysis approach, using a simple list of requirements units (typically referred to as User Stories) and planning no more than the next two weeks in advance. Inevitably, however, they encountered problems as they took on greater challenges – problems that led them to grow their agile BA practice and ultimately, to improve project outcomes.

These, then, are the Top 10 Reasons that these teams have found that they needed to go beyond a ‘bare-bones’ approach to analysis and develop a mature agile BA competency:

1: When the business problem itself is complex, a bare-bones approach doesn’t cut it.

Symptoms: Initiatives characterized by transformative change, complex business rules and/or complex process workflow

When the business problem itself is difficult, the analysis will be difficult as well – regardless of the development methodology. Unfortunately, the adoption of agile does not do away with the need to understand and communicate complex business rules, business processes, data attributes etc. – areas that have been addressed successfully by Business Analysis for many years and that remain useful in an agile context. Agile teams – even those in non-traditional, new-technology businesses – begin to face these issues as they mature and take on more difficult and long-term initiatives such as those characterized by transformational change, process re-engineering, or any technological change that is likely to impact complex business workflows. When agile teams are faced with business complexity, they need to on-board many of the traditional techniques of Requirements Engineering – such as process and domain modeling – but in a way that adapts them for the lightweight, just-in-time, iterative approach of agile.

2: In some important ways, Business Analysis can be even harder in agile than in Waterfall.

Symptoms: Difficulties decomposing requirements for agile (‘Story Splitting’); challenges mapping requirements (Stories) to iterations; recurring ‘bottlenecks’ of requirements units (User Stories) reaching Testing stage near the end of an iteration.

In fact, teams are finding that the need for a mature Business Analysis competency not only remains but can actually increase when an organization transitions to an agile process – because in some important ways, Business Analysis is actually harder to do in an agile environment than it is in Waterfall. One key aspect of agile is that it’s iterative – which means that it involves many iterations of the analysis-design-code-test cycle. From a requirements analysis perspective, this means that the analysis is spread out over the course of numerous passes, rather than being performed all upfront, as it would in a Waterfall process. There are big benefits to doing analysis iteratively, but it also introduces questions that don’t come up on Waterfall projects, such as: When should we analyze business rules? When do we specify tests? When do we do a deep dive on which aspects of the user requirements? The answers to these questions matter, because analyzing requirements too soon or too late introduces costs – and also because on complex projects, we often need to coordinate with other teams that have long planning timelines.

Another reason business analysis can be harder in an agile environment is because it’s incremental. In many agile implementations, this means that the requirements need to be segmented into requirements units that each add an increment of value to the customer. (This is sometimes referred to as Story Splitting. The term refers to the ‘splitting’ of big requests – called epics – into smaller requirements units, referred to as User Stories.) One team, for example, found themselves in a conundrum: any requirement unit (User Story) they designed that was small enough for agile (because it could be implemented comfortably within an iteration) was inevitably too insignificant to add value to the customer. Another team kept finding that its requirements units (User Stories) were often estimated to take almost an entire iteration to implement – and that this left no safe window in case of overruns, while creating a backlog for QA. As these examples show, requirements management in an agile environment can present challenges that don’t exist in ‘traditional’ analysis contexts and call for agile BA competencies (such as being able to decompose requirements into units optimized for agile) that we don’t often find on a team unless we make an effort to include them. (The Scrum Guide makes a passing reference to this reality in relation to the “particular domains that need to be addressed like testing or business analysis.” [17])

3: Agile BA helps compensate for lack of sufficient human resources from the business side

Symptoms: Product Owners/Customers on agile projects are overworked, shared across teams or lack necessary requirements competencies

One of the most consequential aspects of agile is that it requires a substantial commitment from business stakeholders – with the result that there are often not enough Product Managers and business Subject Matter Experts (SMEs) to go around. Agile BAs can provide valuable requirements-related support for these overworked stakeholders.

Coincidentally, as I am writing this, I have just heard from one of our consultants working on a gig with a federal government agency. I asked him how an agile transformation was going there and he told me things were great and that the business side was totally sold on agile. I was pleased to hear that – but much less so once I heard the reason: they believed that agile would mean less work for them (likely due to what they’d heard about agile’s preference for lean requirements documentation). This disturbed me because (as anyone who has been through an agile transformation knows) agile does not mean less stakeholder involvement – it means more – more stakeholders for more time: more stakeholders – because agile approaches typically require about one dedicated business-side decision-maker (the ‘Product Owner’ in Scrum or the ‘Customer’ in XP) for each team of about 7 people; and more time because stakeholders’ time is not just needed at the beginning and end of a project (as it is, largely, for Waterfall) but throughout the initiative. That adds up to a lot of business decision-makers tied up with development for long stretches – and there often just aren’t enough of these people to go around. In fact, many organizations find they only have about 1 such person (e.g., Product Manager) for every 2-4 teams. I’ve seen many different solutions to this problem – including the Proxy Product Owner, the rotating Product Owner/Customer (business SME dedicated but for a brief period of time), and the Product Owner who is shared amongst a number of teams. None of them, however, change the underlying math: insufficient business resources for the required work. Agile BA practitioners (whether or not as a dedicated role) support overworked Customers in carrying out the requirements-related aspects of their roles.

4: Customer/Provider Relationships that are primarily contractual require more comprehensive requirements documentation than collaborative relationships.

Symptoms: Off-shore development, other 3rd party development; corporate governance requirements

Agile presupposes a collaborative relationship between Developers and the Customer – one that does not require specific, contractual obligations with respect to what functionality will be delivered when. In many situations – such as when the Customer is engaging a 3rd party solution provider – this is not a realistic expectation. For example, we work with a company that provides software services in India to U.S. companies. As offshore developers, their relationships with clients tend to be contractual rather than collaborative, and this means that they need to be able to provide comprehensive upfront requirements documentation detailing the features they will be obligated to implement. This is also true in cases where the solution requires a heavy upfront financial commitment from the business – such as the purchase of a COTS (Commercial Off-The-Shelf) software system – and in situations that lock the business into a long-term relationship with a given Service Provider or 3rd party developer. Since the financial commitment is primarily upfront, it dictates that much of the analysis must be so as well.

The documentation in these cases is not ‘waste’; it acts as the basis of a contract and protects the interests of the Customer in future arguments about whether certain requirements are in or out of scope – and therefore who is financially responsible for their implementation. A mature agile BA practice supports the business in the creation of these requirements artifacts to the level of detail required by the situation – and ensures that they are implemented as specified.

5: Large initiatives with multiple teams require mature requirements management competencies

Symptoms: Agile front-end teams waiting for other ‘back-end’ teams to complete work they are dependent upon

Managing dependencies between requirements is one of the great challenges of agile in a large multiple-team environment because the requirements are constantly in a state of flux. It’s hard enough doing this when one team is involved – much more so when there are many interdependent teams. This was the case with one of the teams we worked with – tasked with developing a client-facing front end, but stalled because the team developing the back-end services they needed had delayed work on those requirements. At the heart this problem is a systemic failure to adequately manage and track requirements dependencies – and prioritize them in a way that serves the business. Agile business analysis provides a number of lightweight tools for addressing these issues, such as Rolling Look-ahead Meetings (which look beyond the next iteration for dependencies), Big Room Sprint Planning (where teams gather to the same location to plan their next iteration) and the sharing of team members – as well as traditional Requirements Traceability tables.

Inter-team communication problems are particularly acute when an initiative includes a mix of agile and Waterfall teams. This often results in a heterogeneous approach to requirements – with the agile team using User Stories while the others rely on Use Cases or some other more formal documentation approach. (Often these approaches are managed with separate requirements-engineering tools.) Agile Business Analysis provides the competency to easily move between the two approaches and the ability to convert artifacts from one form to another when needed.

An additional challenge in these circumstances is that Waterfall teams often work on a much longer timeline than the 1-2 weeks that is common for agile. This means that agile teams need to be able to plan much further ahead than the next iteration or two. Agile Business Analysis adds mid and long-term planning tools, like Story Maps and the GO Product Roadmap, to the short-term and iteration planning tools provided ‘out of the box’ by agile frameworks such as Scrum.

6: When there is a soft skills deficit on the Team, agile BAs fill the gap

Symptoms: Any time you wouldn’t put your Developers alone in the same room as the business.

I was just on the phone last week with a high-level exec for a US federal agency that is adopting agile. As we discussed upcoming work, he was bemoaning the fact that he wouldn’t dare put most of his developers in front of a business stakeholder. It was interesting for me – a former developer – to see how little things had changed in this respect from my days in the trenches. For many program and project leaders, this Soft Skills gap is reason enough to include someone with a BA competency on the team – even as they convert the organization to agile. These agile BAs provide ‘people skills’ that encompass facilitation, oral and written communication, negotiating and knowing when to ask the right questions.

7: Dispersed teams and customers require more business analysis

Symptoms: ‘Work from anywhere’ policies and national initiatives with dispersed teams requiring enhanced analysis techniques for requirements communication.

When teams are co-located and have many opportunities for face-to-face communication with each other and the customer, it’s possible to rely primarily on conversation to communicate requirements. But these conditions do not always prevail. It’s now common in large organizations for teams to be working from different locations, sometimes on different continents. Furthermore, in an attempt to lower real estate costs while providing employees with more choice, many companies have adopted flex-time, work-from-anywhere policies that mean that team members rarely meet together in person. These circumstances require more extensive and explicit requirements documentation than is typically provided by a bare-bones agile analysis process.

8: Agile teams are looking for guidance on an end-to-end approach for converting high-level business needs into detailed IT requirements specifications that does not ‘break the value chain’ – especially on major initiatives

Symptoms: Teams that are consistently satisfying system specifications but failing to meet high-level business objectives

Some teams find that they are able to capture the business-side objectives and needs, such as reducing voluntary churn, but stumble when it comes to converting those needs into solution requirements. The result is often that the solution requirements – and in turn, the solution itself – slowly drift away from their initial high-level business needs. These circumstances point to a break in the value chain from need to delivered solution. Agile Business Analysis helps avoid this break by providing a full requirements lifecycle pathway from high-level business goals down to the IT requirements.

9: Agile teams need better tools for managing stakeholder expectations and planning requirements analysis and implementation

Symptoms: Stakeholders become disillusioned when early releases of the product do not address their concerns.

Because agile is iterative, stakeholders rarely get everything they want in the first pass. Not only may they have to wait for some time, but in some cases, things may actually get worse before they get better due to temporary workarounds. Add to this the fact that many stakeholders – primed by years of Waterfall – believe that if something has not been implemented in the first rollout, then it will never happen – and you have a recipe for a potential ‘Expectation Management” nightmare. This was the situation facing one of our clients, as they prepared to phase in a new Geographic Information System used in many business processes and by many stakeholders. The organization had decided that there would be little budget for customization during the first iterations. Good stakeholder management required medium and long-term planning to enable teams to inform stakeholders when the requirements of each group would be implemented – and forewarn them about when to expect temporary workarounds. Agile Business Analysis brings a number of generic and ‘agile-specific’ tools to the table to help accomplish this: the GO Product Roadmap is a light-weight tool for planning the rollout of features over the long term; Use-Case Models and Process Maps help identify impacted users; Story Maps used in conjunction with Lean Startup principles help visualize when and where temporary workarounds will be required.

10: Agile BA supports strategic, data-driven Product Development

Symptoms: The organization needs to improve its use of behavioral data to determine where to target future investment in product and software development

Many organizations find that they’re building the solutions the customer has asked for – but not always investing in implementing the right product and service enhancements. A mature agile analysis practice extends the concept of agile development into the broader Product Development strategy by integrating LeanStartup principles and tools that test business assumptions early, so that investment can be targeted to the right features – based on real evidence in the marketplace.

Mainstream organizations: A ‘perfect storm’ of non-ideal scenarios for agile

If we look at the big picture for agile, the ideal context would be one that resembles a commercial kitchen: It’s run by a tight, small team whose members work in close proximity to each other; the team contains all the skills required to get the work done; most of the communication is informal and oral and very little needs to get written down; there is trust between the business side and solution provider; all teams on the initiative are agile; the planning horizon is fairly short; and customers – those paying for and eating the product – are in frequent face-to-face contact with the team.

Most mainstream business environments are nothing like that. In fact, they are a witch’s brew of many if not all of the scenarios I’ve laid out above: Their teams are not co-located; their teams are not independent but part of larger initiatives with inter-team dependencies – and at least some (if not many) of these teams are not agile. And in many cases, despite a desire to ‘eliminate waste’, extensive documentation is still going to be required due to regulations, governance and accountability issues. Many of these organizations still want to be as agile as they can – but business constraints like these mean they need more than a simple approach to the way requirements are planned, elicited, documented, verified and managed. In situations like these, ‘agile Business Analysis’ acts like Polyfilla – filling in the gaps between the ideal context for agile and the one that actually exists on the ground for many mainstream organizations.

Acknowledgement

Images are original oil paintings by the author, Howard Podeswa. Photography by Toni Hafkenscheid.

References and Literature

- [1] IIBA. Business Analysis Body of Knowledge v3. 2015. 2.

- [2] IIBA. Business Analysis Body of Knowledge v3. 2015. 2.

- [3] Project Smart. The Standish Group Chaos Report, Standish Group, 2014. 3.

- [4] The Standish Group Chaos Report. Project Smart, 2014, 9.

- [5] Ellis, Keith. Business Analysis Benchmark – The Impact of Business Requirements on the Success of Technology Projects”. Toronto, Canada: IAG, 2009. 2-3.

- [6] Ellis, Keith. Business Analysis Benchmark – The Impact of Business Requirements on the Success of Technology Projects”. Toronto, Canada: IAG, 2009. Specifically, it found that an organization with best requirements practices spent on average $3.63 million on a project originally estimated at $3 million while an organization with poor requirements practices paid $5.87 million for a project estimated at $3 million – representing a 62% cost increase.

- [7] As reported by the author, in the online article, “Standish Group 2015 Chaos Report – Q&A with Jennifer Lynch” https://www.infoq.com/articles/standish-chaos-2015

- [8] Ellis, Keith. Business Analysis Benchmark – The Impact of Business Requirements on the Success of Technology Projects. Toronto, Canada: IAG, 2009. 8.

- [9] From a file provided directly by the author on research for Business Analysis Benchmark – The Impact of Business Requirements on the Success of Technology Projects. Toronto, Canada: IAG, 2009.

- [10] Highsmith, Jim. History: The Agile Manifesto. Web. Nov. 12, 2015. http://agilemanifesto.org/history.html

- [11] Ben Linders, 10th State of Agile Survey, (InfoQ, 2016), http://www.infoq.com/news/2015/09/state-of-agile-survey accessed May 3, 2016.

- [12] QSM Associates. The Agile Impact Report, Proven Performance Metrics from the Agile Enterprise. 5. Web PDF. Nov. 14, 2015. https://www.rallydev.com/sites/default/files/Agile_Impact_Report.pdf

- [13] Schwaber, Ken and Mike Beedle. Agile Software Development with Scrum. New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall, 2001). Print. viii.

- [14] QSM Associates. The Agile Impact Report, Proven Performance Metrics from the Agile Enterprise. 4. Web PDF. Nov. 14, 2015. https://www.rallydev.com/sites/default/files/Agile_Impact_Report.pdf

- [15] To download the extension, see http://www.iiba.org/babok-guide/Agile-Extension-to-the-BABOK-Guide-IIBA.aspx

- [16] Ellis, Keith, from a file provided by the author on research for Business Analysis Benchmark - The Impact of Business Requirements on the Success of Technology Projects. Toronto, Canada: IAG, 2009.

- [17] Schwaber, Ken and Jeff Sutherland. The Scrum Guide. 2013. 6. The context is Scrum’s rule that, regardless of the need for competencies like Business Analysis, Team members all have the generic role, Developer.

Howard Podeswa is a thought leader in the intersection of agile and business analysis. For over twenty years, he has been helping large organizations optimize their analysis and planning practices for agile software development approaches. He has authored a number of books that have become staple references for practitioners, most recently: The Agile Guide to Business Analysis and Planning: From Strategic Plan to Continuous Value Delivery - How Product Owners and Business Analysts (BAs) maximize the value of the product developed by the team, by integrating BA competencies with agile methodologies (Addison-Wesley Professional; 1st edition, 2021). Other works include UML for the IT Business Analyst (2009), and The Business Analyst’s Handbook (2008).

At Noble Inc., he has provided agile and business analysis services to clients worldwide, including the International Standards Organization (ISO), Moody’s, the Mayo Clinic, TELUS, TD Bank, LabCorp, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Mawer Investment Management Ltd., Bell Nexia, and REI Coop. He is currently advising IIBA on its Nimble initiative.

To contact Howard for in-house and public training and coaching services, please email howardpodeswa@nobleinc.ca or find him on LinkedIn @howardpodeswa