Gunnar Harde

How Epics Systematically Prevent the Implementation of Core Requirements

A Structural Analysis of Prioritization Pitfalls in Agile Hierarchies

Discover the pitfalls of requirement prioritization in scaled agile frameworks. This article shows how epics and their use in scaled frameworks can systematically delay the realization of critical requirements. It explains why nice-to-have user stories are often realized before the realization of essential stories. The proposed solution introduces a clear distinction between space (the actual specification of requirements and their business contexts) and time (the process of realizing requirements). By redefining epics as spatial entities and introducing containers as temporal entities to manage the development process, this approach provides more effective management of requirements in time and space and supports the early generation of business value.

The Need to Prioritize Requirements

Prioritizing Product Backlog Items (PBIs) is one of the most important tasks of a Product Owner (PO)[1]. A backlog sorted by actual priorities and an implementation sequence according to this prioritization ensures that business value is generated as quickly as possible. Prioritizing requirements is thus one of the key success factors in product development.

Agile frameworks like Scrum[2] or Kanban[3] demand that the team focuses on implementing the highest priority requirements – by defining the sprint backlog for the upcoming sprint based on the sorted product backlog or by limiting the Work in Progress (WIP).

Scaling the Organization

This works well if the most urgent PBIs have been broken down into development-ready PBIs (i.e., Ready for Sprint in the sense of Scrum) and these have been prioritized. This is easy to do with a small product backlog managed by a single PO who delivers requirements for one or very few teams. It becomes more difficult when many teams are to implement many requirements for a large product, so that no single PO is able to manage the entire product backlog in detail.

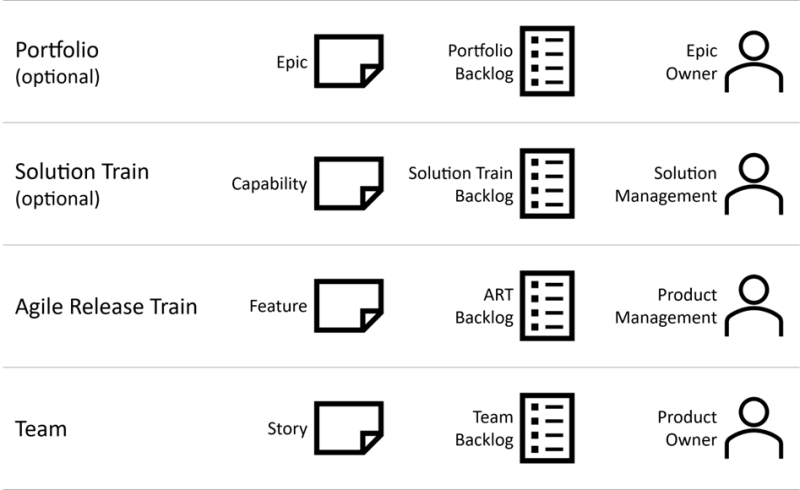

A common approach to managing such complexity is to introduce hierarchies: of requirements, of backlogs, of POs. This is how the Scaled Agile Framework (SAFe) works [4]. Multiple agile teams, all with their own team backlog and PO, implement the requirements defined by the higher-level hierarchy – called agile release train (ART) – with their own ART backlog and product management. This can be extended up to a four-tier hierarchy (see Figure 1).

In the following, the discussion is limited to a two-level hierarchy without loss of generality; a transfer to more levels is straightforward. In addition, the term story is used for the smallest unit of requirements and epic for the next higher level, as these terms are more common in the agile community than those of the very SAFe-specific terminology. According to the terms used here, the Chief Product Owner (CPO) manages epics and is responsible for maintaining the Product Backlog, while Product Owners (POs) manage stories and maintain team backlogs.

The distinction between epics and stories and their separate management has several advantages:

- The CPO can discuss initial ideas for new functionality with stakeholders at the epic level without diving into details that are unlikely to be helpful at this early stage.

- The CPO can see the big picture and prioritize epics according to overall business goals.

- The CPO and other managers can track the realization of requirements at the epic level and get a good overview of the realization status.

- The PO, who is familiar with the affected product component, derives the stories from the epic. Detailed discussions are thus left to the experts.

- Stories are linked to their epics, which makes the context of the stories and the general meaning behind them apparent. Stories describe the specific requirements without the need to repeat the purpose at a higher level.

These benefits exist also if the organization does not reflect the different flight levels of epics and stories. Even a single PO could use epics to communicate with stakeholders, track requirements, and describe the context of stories on a higher level while discussing details at the story level.

Failing Prioritization

Requirements should be prioritized at the user story level: ‘Based on the value/effort ratio the Product Owner can select the stories that should be taken on by the developers in the next iteration.’[5, p. 71]. Nevertheless, to make it easier for management to trace progress, prioritization usually takes place at the epic level in practice. This is also recommended by scaling frameworks based on flight levels, such as SAFe. SAFe, for instance, requires the identification and scheduling of high-priority epics for the upcoming interval, and suggests tracking epics using a Kanban board[6]. This leads to a systematic postponement of high-priority stories and thus undermines the goal of realizing the most valuable requirements first:

Nice-to-have stories that are derived from a high-priority epic in addition to crucial stories block the implementation of valuable stories that belong to epics with slightly lower priority.

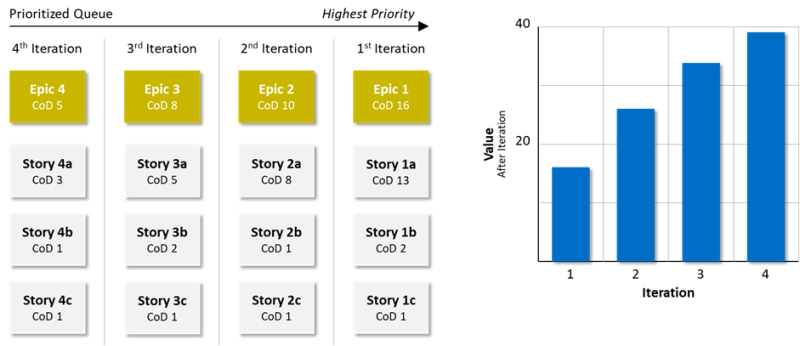

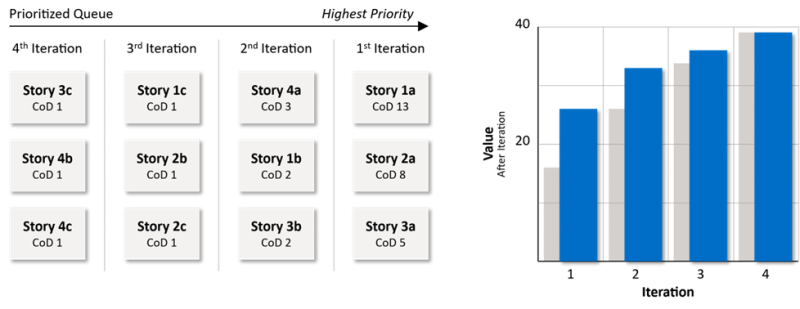

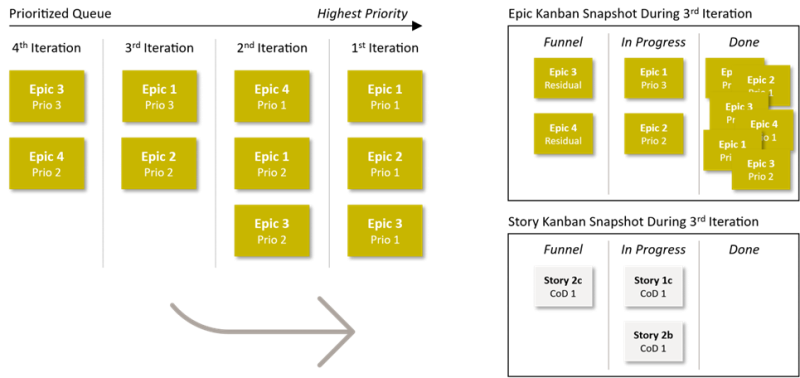

This is illustrated in the example scenario outlined in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2 shows four prioritized epics, with epic 1 being the most valuable and epic 4 being the least valuable. For simplicity and without loss of generality, it is assumed that three stories have been derived from each epic and all these stories require the same implementation duration. Therefore, the assessed Cost of Delays (CoD) for the stories can be considered as the Weighted Shortest Job First (WSJF). The CoDs for the epics are determined by summing the CoDs of the assigned stories. Further, it is assumed that three stories are realized in one iteration. The cumulative business value after each iteration is shown on the right-hand side of Figure 2.

Figure 3 describes the situation when the implementation sequence is based on story priorities instead of epic priorities, on the assumption that the user stories are independent of each other. The blue bars showing business values increase faster than the gray bars showing growth when epic priorities are determinant.

The greater growth in business value in the case of story priority orientation has several advantages:

- The developed solution is more useful to users in the early stages and therefore can potentially generate more profit early on.

- The solution might be used earlier and therefore lessons learned for upcoming development can be gained sooner.

- If the budget is limited, the risk of not developing critical requirements is reduced.

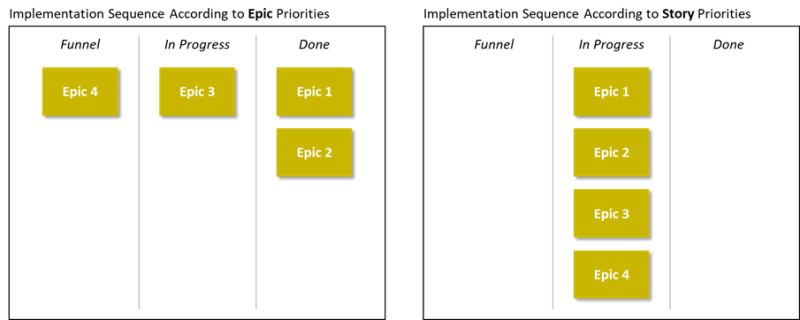

However, focusing solely on story priorities has one key drawback: the loss of transparency at the epic level. This is illustrated in Figure 4. Shown are two snapshots of (simplified) epic Kanban boards during the 3rd iteration based on the previously presented scenarios: on the left an implementation sequence according to epic priorities, on the right according to story priorities. A realization based on epic priorities provides a clear picture of the states of the epics. However, this is not the case with a realization based on story priorities: In the example, all epics are in the state of realization because at least some of their stories are in progress or already realized, but none of them have all their stories done. In general, implementing according to story priorities results in epics being stuck in a fuzzy WIP state, with no real overview of what has already been delivered and what is still waiting in the funnel and thus could be reprioritized, changed, or removed.

Solution Approaches

The distinction between the more general epic level and the more detailed story level leads to the dilemma of not being able to generate business value as quickly as possible while still clearly tracking the status of the epics. The first approach to solving this problem is to split the epics over time into “sub-epics” that contain only the stories with the highest priority at that time and the remaining stories of lower priority, as exemplified in Figure 5.

Although the number of epics has increased, stories are continuing to be bundled together and can be followed on the upper level as a thematic package without having to dive into the details on the story level. However, this approach has a drawback: the overarching requirement described in the original epic is now distributed and copied across multiple sub-epics. The purpose of an epic is to enclose the stories and provide context. Managing this context across multiple sub-epics would be challenging and could lead to inconsistencies.

Therefore, it makes sense to keep the original epics as the context of the stories and additionally introduce sub-epics according to the priority of the stories. At first glance, this would result in a three-level requirements hierarchy, but the character of the epics and its sub-epics is fundamentally different: epics describe the space component of a requirement, while prioritized sub-epics describe its time component.

Space and Time

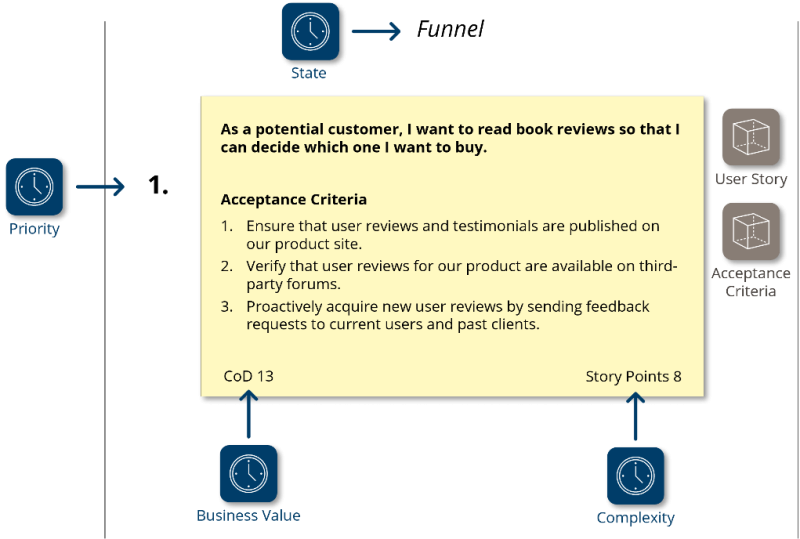

Requirements consist of different types of information. These information types are assigned either to space or to time: They tell us how a requirement is processed in time, or they describe in space the actual requirement (Figure 6)[7].

Typical space information types are user stories, acceptance criteria, use cases, workflow diagrams, class diagrams, and mockups. Typical time information types which help to pass backlog items through the development process are state of the backlog item, timestamp of changing states, priority of the backlog item, assessed business value (e. g. CoD), assessed complexity, assessed job duration, WSJF, requiring stakeholder(s), team assignment, and editor.

Stories in this sense are compact in space and time. A story describes a single well-defined requirement, including its purpose (compact in space), and it should be realized within an iteration of a few weeks (compact in time). Epics are different: An epic defines a requirement at a higher level, but its realization could be spread over a longer period of time. The common interpretation of epics as requirement descriptions and at the same time as traceable units in the development process is the root cause of nice-to-have requirements being realized early and more important requirements being postponed. The key to solving this problem is therefore to distinguish between space and time: Epics are spatial entities that describe high-level requirements and provide context for their stories; epics are not temporal entities and are not suitable for planning or controlling the development process. Something different is needed for process-oriented tracking of units larger than stories.

For this reason, the term container is introduced and defined as follows: A container is a group of requirements that are functionally related and should be implemented together in a short period of time. One or more containers are temporal counterparts of an epic. A container can be initially empty and dynamic in composition. A container should be implemented in one or a few iterations. However, they are generally not sprint goals. Because of their temporal nature, containers are elements of a roadmap, not a specification, where epics belong.

The distinction between time and space is also described in the IREB RE@Agile Handbook, which distinguishes between a special ‘product-focused backlog’[5, p. 96] and a roadmap[5, p. 105].

Epics, Containers, and Stories in Practice

The use of epics, containers, and stories and their interactions are demonstrated in the following example.

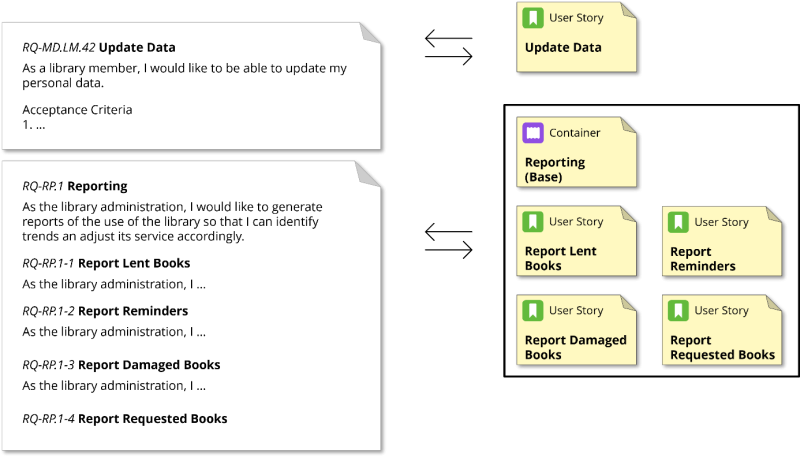

In this example, a library system is being developed. The PO of this system gathers requirements by interviewing library operators and other potential users. After one of these interviews, two requirements have been captured: updating personal data by library members and generating reports by the library administrator. The reporting requirement consists of a list of different types of reports, which are sub-requirements. The product owner describes the requirements in a document management system (left side of Figure 7), adds backlog items in a tracking system (right side of Figure 7), and links these items to the corresponding specification in the document management system. Thus, the requirements (epics and user stories) are described in the tracking system using the well-known user story formulation. This can be done either directly or by referencing the requirement in the document management system.

Here, the PO, after consulting with the development team, assumes that Update Data can be implemented within one iteration, so there is only one user story representing the requirement in the tracking system. In contrast, the Reporting requirement is an epic. It is initially represented by a single container that contains user stories for each of the report types identified so far.

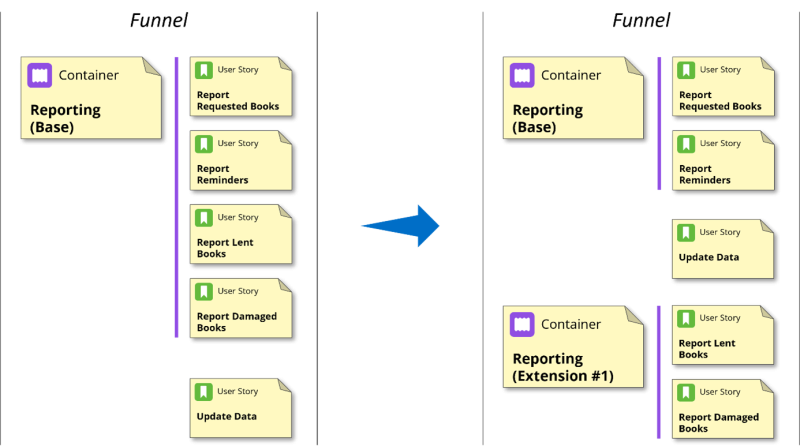

Next, the PO prioritizes the Product Backlog. First, he decides that the Reporting (Base) container and all its stories should be implemented first, followed by the Update Date story. But then he changes his mind due to new information. He values some reporting types less than the Update Date story. And this is where the distinction between epic and container comes into play: all report stories remain part of the Reporting epic, but are distributed across the Reporting (Base) and Reporting (Extension #1) containers as shown in Figure 8.

Conclusion

The common use of epics in scaled agile frameworks often has the unintended consequence of delaying the implementation of critical requirements. This problem arises because high-priority epics can contain nice-to-have stories that are prioritized over essential stories from less critical epics. To address this, it is important to distinguish between the spatial specification of requirements and the temporal process of their realization. Epics should be used to define the scope and context of requirements, while containers should be introduced to manage the temporal aspects of their implementation. This dual approach ensures that the most valuable requirements are addressed in a timely manner, increasing overall business value and improving the efficiency of agile development processes.

References

- [1] M. Iqbal, "Prioritization Techniques for the Product Owner," 28 August 2023. [Online]. Available: scrum.org/resources/blog/prioritization-techniques-product-owner.

- [2] K. Schwaber and J. Sutherland, "The Scrum Guide: The Definitive Guide to Scrum: The Rules of the Game," 2020. [Online]. Available: scrum.org/resources/scrum-guide.

- [3] D. J. Anderson, Kanban: Successful Evolutionary Change for Your Technology Business, Blue Hole Press, 2010.

- [4] C. M. Cuenca, "Enterprise Backlog Structure and Management," 3 April 2023. [Online]. Available: scaledagileframework.com/enterprise-backlog-structure-and-management.

- [5] P. Hruschka, K. Lauenroth, M. Meuten, S. Gärtner, H.-J. Steffe and R. Gareth, "Certified Professional for Requirements Engineering - Handbook RE@Agile Practitioner | Specialist," 2024.

- [6] "ART and Solution Train Backlogs," Scaled Agile, Inc., 9 October 2023. [Online]. Available: scaledagileframework.com/art-and-solution-train-backlogs.

- [7] K. Lauenroth, Interner Workshop adesso - Requirements Engineering im Projektkontext, Essen, 2022.

Gunnar Harde is Principal Consultant at adesso SE. In conjunction with his clients, he is responsible for their requirements engineering in critical software development projects.

He has many years of experience as Product Owner and Chief Product Owner. With over 25 years' experience in software development and organizational consultancy, he offers in-depth expertise spanning a variety of sectors, including automotive, healthcare and market research.

Gunnar studied physics in Germany and New Zealand. He now lives in Hamburg.